Wines and vines with altitude. After joining the first Meili Snow Mountain International Wine Festival and giving a speech at a forum on the potential for the area’s wines, we headed off on the region’s long lofty narrow winding roads to visit some vineyards.

Before arriving in Yunnan, I was unsure which producers we would visit, and was intrigued with Xiaoling (I’ve been tasting their wines for almost a decade) and Zaxee (which makes delectable Chardonnay at a decent price). It turned out we headed for two different and worthy operations, Ao Yun and Bao Zhuang, with the former by LVMH and the region’s most internationally prominent winery and the latter getting much attention the past year or two, including high praise from Nanning-based expert Julien Boulard.

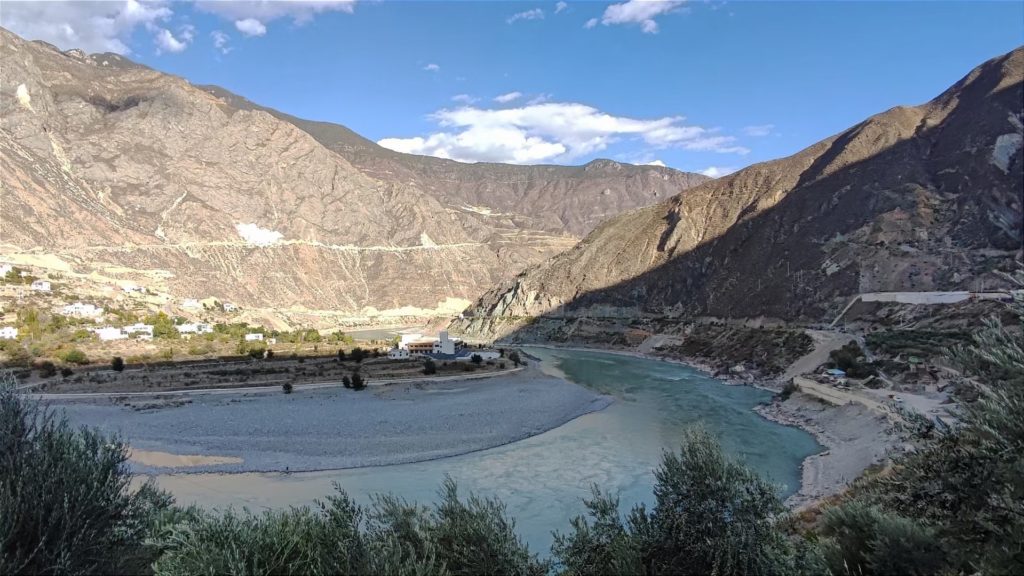

As noted, the drives between vineyards followed long winding high and sometimes bumpy roads, though these are far better than a decade ago, while offering stunning views of imposing mountain ranges, deep valleys and meandering rivers.

We first visited one of Ao Yun’s vineyards, Shuori, which is set partway down a valley at 2500 meters, with a Mekong tributary winding below.

Ao Yun’s Alex Zhang said this site has Cabernet Sauvignon dating to 2004, plus newer plantings, and that some varieties are intermingled. The 100 mu / 6.6 hectares of vineyards are managed by 14 area families, with guidance from the Ao Yun team.

Zhang said Ao Yun’s four vineyards include just over 300 blocks, further divided into ~700 sub-blocks, with a flag system used to indicate each parcel. One tiny area we saw, with a half-dozen rows of vines, constituted two terroirs. And unlike in much of north China, there is no need to bury vines for winter.

Both drip irrigation and flood irrigation are used. The latter is done three times per year: before winter, before bud burst and before flowering. The water comes not from the river below but the mountains. Unlike in some regions where wineries pay for water, it is free here, says Zhang.

This was a visit both informative and idyllic given our stroll in the warm Yunnan sun, the diverse flora—persimmon, pear and peach trees, among others—and the occasional rustle of falling fruit or soft bark of a distant dog in the village.

When I posted these photos online, I received this one of Shuori in 2009 from a man who accompanied Australian oenologist Tony Jordan on his trips around China in search of the best place for LVMH to make its wine. More on that in a later issue.

We then went on another long and winding journey to the winery of Ao Yun, which translates to “flying above the clouds”, to tour the facilities and taste the 2018 vintage.

The vineyards here are set majestically in a valley, with barn-shaped winery buildings and guest facilities perched above. As with other Ao Yun sites, precision viticulture is the game, and includes multispectral cameras mounted on a facing slope to monitor the vineyards.

Ao Yun, which had its first vintage in 2013, is overseen by Maxence Dulou. Manager Peter Dawa Pinchu says the winery still isn’t open for casual visitors, as the team wants to perfect everything, but hopefully this happens soon.

He led us on a tasting of four 2018 wines that displayed a blend of fruit, tannins, balance and complexity that international critics—or those who aspire to be international critics—tend to love. And in this case to compare them to what Bordeaux has to offer, much as with Lafite’s Longdai in Shandong province.

The Ao Yun flagship wine features pure fresh black cherry with notes of toast, nuts and light earth. The fruit is a bit wild, let’s call it youthful, but with restrained tannins, and blackberry and spice character at the finish.

A visiting winemaker at our table declared it one of the world’s best wines. I was surprised given that I wasn’t sure it was the best wine I’d tried that week.

Xidang, named after one of the four vineyards, had more complex aromas, including fresh roses, ripe dark fruit, and chocolate, toast and something umami-ish lurking. Smoother and easier drinking, this one had a pleasant tart edge, somewhere between raspberry and hawthorn.

Shuori, from the vineyard we visited earlier, also had fresh rose aromas, but lighter fruit and also whiffs of graphite. Fresh and juicy, even a bit “chewy”, with lighter tannins and a softer finish. (Cranberry and yangmei in place of Xidang’s raspberry and hawthorn.) The seems less likely to be loved by experts but more versatile for a mixed crowd.

Finally, Adong came out swinging, with dark vibrant fruit, whiffs of violets, vanilla, candle wax and toasty oak. This one morphed in the glass, throwing off all kinds of aromas, including graphite, menthol, maybe even a hint of A-535 (!). Juicy and voluptuous, with dark purply fruit.

What does all this mean? Not much, as my notes are generally all over the place.

But I can say that while I enjoy these wines, and they got superb reviews from our group, I kept thinking about being in such a wondrous high-flying unique place while judging its wines based on the standards of another continent and culture and in comparison to foreign regions. For that is what much of the wine game in China feels like: how does it stack up to international norms that are pretty much European.

A natural rejoinder is one can both compare such wines to, say, red blends from Bordeaux while seeking how they capture the local “terroir.” Yes, one can, I suppose.

Anyway, in the end, world-class wines by a world-class team that was incredibly informative in both the the vineyard and winery. At the end of the day, good wine relies on good people, and LVMH gets high scores here.

Our last stop, after lunch, was to Bao Zhuang, which is attracting attention for its Celebre label, including from Julien Boulard, a well-known critic based in Nanning.

In April, Boulard asked himself if China’s fine wine had reached the level of other countries’ fine wines, and his answer was no. Then a short time later he tasted Celebre.

“Of all the Chinese wine I’ve tasted, I’ve never drunk a wine with a score of 92 or more by my standards,” he posted on WeChat. He added that if any wine could reach 95 points, it must be from this producer, and later confirmed this with further tasting of Celebre and other wines from Bao Zhuang.

Celebre also stood out during the official 11-wine tasting at the festival. It was juicier and more intense than the others, with a kind of dark raspberry jam edge, but still balanced.

“The closest thing we’ve had so far to a fruit bomb,” I wrote in my notes, with someone else mentioning California. I’ll follow-up on this wine with Boulard, who also talks at length about how some Bao Zhuang wines feature very localized aromas and flavors.

In any case, Bao Zhuang is beside a river curve, near a pretty busy road, with tanks set outside. I should have asked about the impact of sun and temperature on the wine inside the tanks but was done after a long day of high-altitude fun.

We tried three wines, starting with a Cabernet Sauvignon Rose: a very light fruit aroma, with hints of red berries and candy apple, and summer flowers. Fairly juicy and easy drinking, with light tannins and a touch of pepper at the finish. Nice.

Then a Rose Honey 2018, a grape that producers have struggled to make palatable in wine form. This one featured aromas of dried roses and ripe Bing cherry, was quite juicy, and had more acidity than I expected—the rose honeys I’ve tried have typically been flabby. There were flashes of intense red fruit and a slightly savory and spicy tart note at the finish. As mentioned, this particularly Rose Honey has been popping up at the kind of wine bars in China that attract the more curious wine consumer. (Someone said this wine might include other grape varieties, something I need to check.)

Finally, the Celebre 2018, a Cabernet Sauvignon weighing in at 14.5 percent alcohol and aged in new French oak. Deep intense fresh dark fruit, with hints of mint, dry grass and milk chocolate. Restrained but juicy and youthful, with lovely texture: something both beginners and aficionados could appreciate.

This one took me back to the festival tasting: it was the wine that made me go “huh?”, that generated some back and forth within our group, the one people said leaned more Napa than Bordeaux.

Uh oh, those comparisons to distant regions again! But of course, Celebre embraces the local terroir. Just don’t ask me how. My pen was retired at that point as I enjoyed the last wine of our trip. I just know it was nice to have that lingering taste of dark fresh fruit on my tastebuds, the taste of something different, as I headed to the bus for our final long winding road trip, this time to back to Shangri-La City.

Sign up for the Grape Wall newsletter here. Follow Grape Wall on LinkedIn, Instagram, Facebook and Twitter. And see my sibling sites World Marselan Day, World Baijiu Day and Beijing Boyce. Grape Wall has no advertisers, so if you find the content useful, please help cover the costs via PayPal, WeChat or Alipay. Contact Grape Wall via grapewallofchina (at) gmail.com.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.